Most fiction published is genre fiction. I am tempted to say all indie-published fiction is genre fiction, but I suspect there are some literary fiction authors who, failing to get a traditional publishing contract decide to self-publish. Still, genre fiction is the bread and butter of indie, so you are much less likely to see the heirs of John Updike or Margret Atwood in KDP than you are to see the heirs of Lawrence Block, Stephen King, Georgette Heyer, Janet Daley, and Robert Heinlein.

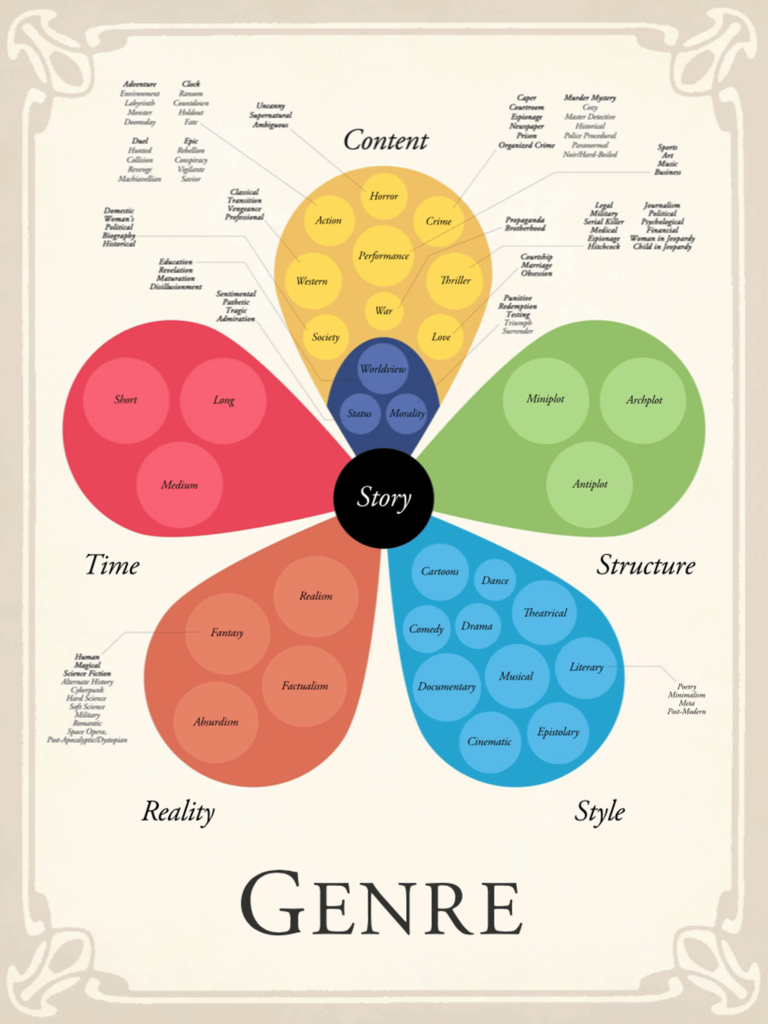

Recently I have had a large change in my view on genre, driven by Shawn Coyne’s book The Story Grid. Specifically, I have been impacted by his ideas on the five-leaf clover of genre.

Looking at it, you can see genre, in Coyne’s world, is built of five things. Content is the one we most often consider genre, but if you look closely two common popular genres are missing, science-fiction and fantasy. They are reality genres, not content genres. This explains two things that had long confused me.

The first is the classification of works most people would not consider science-fiction as science-fiction. You will not find 1984, Brave New World, or The Handmaid’s Tale. shelved with science-fiction, but they are often described as such. In fact, early college science-fiction courses had little shelved in that section but had literary novels with a mildly futuristic setting. This idea, that science fiction is from the reality part of genre that allows for any type of content genre. This is how worldview and status novels, as I classify those three, can be science fiction.

Second, it explains the changes in science-fiction and fantasy as genres over the past few decades and how those changes have alienated a lot of fans. If you search by genre on Amazon and sort by sales, many fantasy subgenres top ten are dominated by romance novels. Urban fantasy is the obvious one, but even some science-fiction genres are ruled by romance or the three interior content genres of worldview, morality, and status.

Historically, science-fiction and, to a lesser degree fantasy, came out of the pulps telling mostly action stories with a good bit of horror thrown in. In fact, as sales genres, science fiction, horror, and fantasy were one and the same, the weird tale of the pulps who take their name from the highly regarded magazine of that name. Identifying this change, and the huge unserved market it left, is how Peter Grant and Pam Uphoff, to name two writers who did it, sold me on reading indie.

It also has allowed me to understand why I haven’t liked a Hugo winner in over a decade, but reread books like The Coming of the Horseclans and The Man Who Never Missed. While fantasy and science-fiction reality genre, they are action novels in terms of content. Not everything I love is action, but a good deal of it is.

More importantly, what I’m trying to write is. While I’m more inclined to the later of those two books which also has elements of a morality tale instead of the former which is pure adventure, I’ve realize action and western novels are at the core of my desire to write.

Learning what kind of stories you want to tell is crucial to understand how to tell them so they satisfy you and the reader. While genre is crucial for the business side of writing as well, in terms of building an audience, before you can draw them in you have to learn to tell the tales that will satisfy them.

[…] is stories are never just “action stories” or something else. It is easier to see how other genres have moral aspects. The morality internal genre is strictly about it. Horror, and its offspring, the […]